Robotics

At the beginning of Sophomore year, I had come across a stand that was not getting much attention during our club fair. It was the Robotics team, and I was skeptical as to what this club actually did. My experience with the robotics team in middle school was rather bland; the plastic parts and block-building coding language, known as "Sketch," left much to be desired. Nonetheless, I was gradually drawn in by the conversation. As the President of the small club gave his presentation, he clumsily fell over once or twice from his stool, but the large jumble of metal, wires, and sprockets behind him had already convinced me of the club's authenticity.

The team was almost entirely seniors, except for me and a Junior, at the beginning of the season. Before the start of the competition, I had built a cart for the robot, and in doing so, I had become familiar with the tools and various resources used for production. We had one person for design, two for coding, three for building, and one or two members who were essentially there for the company. Through this small group of engineering enthusiasts, I first met Dr. Pav, the incredible physics teacher at my school. The meetings would take place in the back left corner of his physics classroom. Often, it would overlap with the astrophysics club's meetings at the front of the room. In this way, we were able to sit in on many curious discussions while attending to our own goals. The room had, and still does have a numerous amount of toys meant for students to interact with an naturally ask questions about the phenomina that the objects exhibit. Between the physics room's partition and the chemistry class was a closet/kitchen room with two doors, inviting the two differing courses. We'd often close this door due to the screeching sound of metal, but in the chemistry room was the neuroscience club. This was my first exposure to this community, but it would not lead to my joining until my Junior year.

My chemistry class was the last class on my schedule, in the 8th period. I had opted to learn cybersecurity instead of attending a study hall so that I would take the long, hot walk across campus from the computer science room, situated in an opposite building across a parking lot and football field, to the science hallway. I would always arrive about 6-7 minutes late, sweaty, and fatigued. Nonetheless, the discomfort quickly went away as the lesson began. I really enjoyed all of it, as each lesson felt fresh and completely different from the others. On Thursdays I would go across the hallway from the chemistry room to the physics to join the robotics meeting, now on this particular winter afternoon the robotics team was gathered in the science hallway. This was so that we could test the robot's capacities and the new swerve drives installed over the previous week. Mr.Crafton, my chemistry teacher, had already taken notice of my activities within the robotics club. Today, he had stayed behind, and in returning to his classroom, he had been sidetracked by the whirring robot and the intently focused group observing its movement across the puzzle-piece foam matte. He came and greeted Dr.Pav before heading back to his classroom. He mentioned the need for a robot for the science olympiad club. By this point, they were past regionals and were heading to state. To gain a competitive edge in the robotics portion of the event, they requested that someone design and create one for their next tournament. Mr.Crafton gave me his word that if the team were able to bring back any medals he would include one for me I had about a month to deliver on the robot.

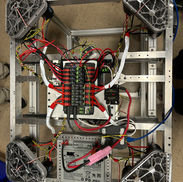

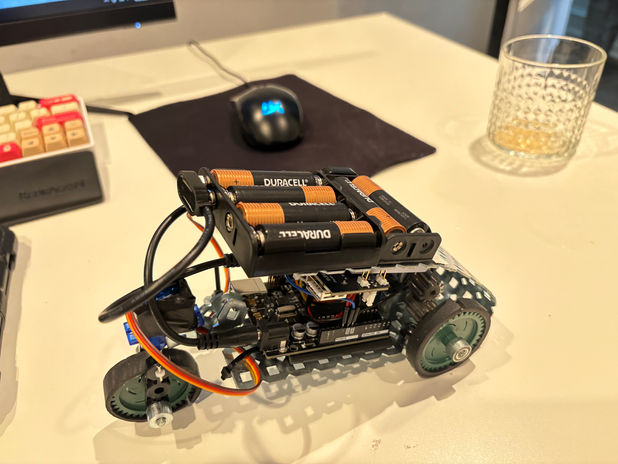

This month also overlapped with Ramadan. I was fasting at the time, with no food or water for the whole day, and the challenge seemed monumental to intertwine with my more than fair share of classwork. I was barely getting through a typical day, as my mind was having a rough time combing through the information I was receiving as a result of the extensive periods of nutrient deprivation. I was foggy the whole day. I would come back home and nap. Then I would eat at sundown and gain a huge energy boost to finish off my work. Now, leading up to the deadline, I spent my time predominantly focused on schoolwork, but I also began to lay down theoretical infrastructure. I was researching how to create a small robot that can maneuver a set of obstacles, as is the parameter of the competition. The previous summer I had learned arduino through a set of instructional videos by Paul McWhorter. They were a perfect complement to this project, but the real firepower came from the resources Dr. Pav provided me. I had multiple large crates of previously used Vex robotics parts. They had certainly not been utilized for any High School Vex competition in a while, as evidenced by the film of dust coating their exteriors. By the time 2 weeks were left, I began to construct the robot.

I had opted for a simple design, seeing that the deadline was fast approaching. This means that I would not use a PCB, but rather a mini breadboard to accommodate the various inputs from the Arduino. The most significant points of fault then were torque, battery consumption, and wiring. To address the loose wiring that often accompanies breadboard designs, I folded the metal into a taco-like shape to encase and provide a force that would keep the wiring stable when the breadboard is attached to the top and the Arduino is connected to the bottom. This initial design used a mini DC motor. These do not provide enough torque, as the restraint from the battery (which limits us to a maximum of 6 double AA batteries) leaves the DC motor with an insufficient amount of torque production. This meant I would have to use a motor with torque in mind. Now, as you can see in these pictures, I had not yet fully loaded the product and thus had no clue at this moment that the motor would be insufficient. I would, however, approximately 2 days before I had to deliver the robot. Now, as with most projects, the last two days seem to be the exponential maximum, where the task consumes and sacrifices all other school work or social activities. Over the past two days, I have been going back and forth, searching for a solution to a simple rule in the tournament guidelines. It stated that a computer may not be used in reuploading programs onto the robot. This meant I would need to use an Android device with the Arduino IDE installed on it. I searched extensively on this point, even using the President of the Club's personal Android device to attempt to download the IDE at one point. This, however, did not work, so I looked at the almost decade-old Android tablet my Uncle had. It was incredibly outdated, and I would have had to download a very obsolete version of the Arduino IDE from the internet to compensate. It was crashing constantly and failed to keep programs in memory. Things seemed rather bleak at this point; only one night was left, and the robot could not move, not just due to torque issues, but also because the battery's wiring was failing to provide power due to wiring problems. I had installed a Vex motor to solve the torque issue; however, it required essentially "tricking" the breadboard into interacting with it as though it were the aforementioned DC motor. The small breadboard had an L293D chip installed to translate commands through pulse width modulation. There was a power split between a wire connecting the arunido and the power supply module that was connected via the ground rail. To make it all work, I would have to break the conventional wiring that I had. I had never sautered before, but I had theorized that if I could make the robot's batteries connect via a second cable branching off the first, (I know very sketchy) that I could get enough power for all purposes.

I dropped the robot off the morning before I headed out to tend the FRC robotics tournament in Huntsville, Alabama. The competition name for the year was Crescendo. I was filled with pride and content at the accomplishment, and after I began the 4-hour drive through the Southern landscape with my friend. The robot was barely able to work on time and came in 6th place at the competition out of around 30 schools. We communicated and made final tweaks over the phone the morning of the competition to ensure it would work well. The biggest fault was actually a wooden dowel that had to be attached to the robot before its release; nonetheless, it wasn't bad.

Vice Presidency Junior Year

We began the year as understaffed as possible for a club. All the seniors had left for college. What was left was a Senior and me. We made an effort during the club fair to present the robot, and we gained a few new members, but the real driving force would be the new senior acquaintances I would make. Keaton was a student in the same AP Physics class as I. We sat next to each other and naturally became acquainted. During lunch time, we had gotten into the habit of skipping lunch and working on our physics problem sets. This was where I met Zander; he was in Physics II. We would spend much time in this room together over the course of the year, and naturally, he joined robotics very quickly. Zander was leading the building of the robot, and Keaton specialized in coding. I was working on everything. One afternoon, I would work on the radio with Zander, and the next, I would work on coding with Keaton. The issue was that a generally large knowledge gap remained in the club. We spent a great deal of time reinventing or rediscovering the basics of robotics, but we did, because we had to.

FRC robotics kicks off the competition at the beginning of the new year. This means that every team has half a school year to prepare for the general procedures that must be followed to build a robot in 3 months, once the competition has started. Though we were focused, we were by no means organized. We were so entrenched in understanding the multifaceted process of troubleshooting and learning. So when the competition started, we had not done any practice for building. The first month was spent with great dedication to fixing the swerve drive issue. We did not know at the time that the encoders were a significant issue, but had figured by then that the new year's updated swerve library was different from the 2024 library we had been using. During this time, I was trying to reinvent the wheel. I tried to use a novel approach to creation rather than conforming to the laws of competition. What I mean by this is I did not want to reference the work of other teams; I really wanted to create a robot that was itself new. This would be a completely unnecessary process. One of the rediscoveries made was for the lift. We took into account the mechanical advantages of pulleys and created a pulley system that was not new, but certainly reinvented by us. I achieved this by disassembling a component of my 3D printer at home, which I had noticed used a sliding wheel that gripped the grooves of the metal frame. This metal framing was very similar to that which we had available in robotics. As time squeezed pressure on us, we would regularly leave the school building when there was no one left in it, and the sundown hours would pass. This was not necessarily new for our robotics team; we had never cracked the issue of being efficient. Typically, everyone in robotics is interested in the robot itself, rather than the organization of effort. For a team that was not as progressed as ours, we were definitely ignorant of the underlying system we had to implement. Nonetheless, we persevered; school had become a secondary interest, and every hour of the day was spent focusing on robotics. This kind of obsession is truly comforting; you get to remove yourself from all other events and specialize in and familiarize yourself with a single objective, no matter how complex it may be. Tunnel vision takes hold of your actions and values. At the end of it, you're left a little dazed and confused as to how 3 months of your life have already flown by. When spring break arrived, we were certainly nowhere near completion, despite our tremendous efforts. We had spent much time trying to troubleshoot the swerve drive, and now we had to switch gears to catch up.

Over the days leading up to spring break, I packed a few hundred pounds of materials, including cutting tools, metal, screws, electronics, and wiring, taking whatever could be needed. Every hour of my spring break that wasn't spent sleeping was spent trying to fix the swerve drive or adding to the mechanical creation of the robot. I had a few members stay the entire day to get the robot running. We were hoping to have it fully completed by the end of spring break, and we got damn close.

Please click on the picture to go into a fullscreen veiw mode and click the arrows to the sides to veiw more.

Vice Presidency Junior Year

We had done everything possible to try to understand the issue with the swerve drive. This week was a highly concentrated effort, and it was sobering. There is something about physics and theoretical work that sedates you into a state of perfect harmony and reason. In engineering, you're cast back down to Earth; your efforts often seem to be nothing but twirling —a dog chasing its own tail, not knowing just how close or far away it is. Well, we eventually packed everything up and arrived at the competition. As is usual for these competitions, there were teams with great robots, faculties, and financial backing. We have been the underdogs since I joined, but I have never minded; you get to create something from nothing. We were in deep trouble with the issues involving the swerve drive; it took 48 hours, with the help of senior coding, engineering adults, and students from the best teams, to thoroughly diagnose and fix our swerve drive. These were the first two days of the competition. It was the end of the power-law progression of our efforts—a valuable lesson in the importance of organization and delegation. Our robot went on to work; however, our contraptions had been largely untested.

Eventually, the torque overpowered our designs, and our robot disassembled itself amidst the competition. We could do little but laugh; despite everything, it was an exhilarating and fulfilling experience. To delve into something that seems insurmountable and see it through to its end, having put in all that your time and efforts might afford, fulfills you like nothing else, no matter the outcome. This was my first time being cast into a truly challenging leadership position, and I'm glad I got to witness the beauty of the fire and smoke that results from watching your efforts crash and burn. My science Olympiad robot from the previous year got 3rd this year.

Presidency Senior Year

I have learned a great deal in the past year. The dispersion of knowledge is crucial to teamwork; all members need to have agency over their own acuity and understanding. Once the learning is out of the way, resources must be allocated, and timely matters must be resolved so that all team members can understand their role within the overall ecosystem, as a team, and as individuals. In this way, all manner of effort towards the fruition of the final whole may be executed. We currently have about 30 members, whereas we had approximately 15 last year and around 10 the year before that. I have pushed to include all underclassmen who might feel they are unequipped with the knowledge or experience for the undertaking. I believe that the health of the ecosystem matters more than individual strength, and in this way, no individual may feel lost, but rather have a system by which they can learn and contribute to their own respective team. This allows higher management to do their job and not get caught up in the immediate details. This way, both future and immediate goals are met, and all disciplines are assigned to these goals, which are then reinforced with guidance from more senior members. Now I doubt robotics at Franklin High School will be overstaffed anytime soon. Still, I've noticed that in companies that do such things professionally, such as SpaceX, they may sometimes have a pool of talent that is too large to meet any sectioned-off goal.

The best solution I've seen is this: The invention of the self-landing rocket was already considered in NASA's 1990s program. It was scratched, but later reintroduced by Edward J. Jacobs at his request to investigate the subject. At first, he made fun of the SpaceX members when they watched his attempts fail, but eventually he began to succeed and went on to lead the Starship program. I've mentioned this information to state that, although I won't be able to carry robotics at the high school level through to truly experiment with novelty, as there isn't enough time, I am not unaware of the direction in which engineering undertakings and organizations are headed. Complexity leads to novelty. I wish to take full advantage of all that engineering has to offer at the college level.